Malaysians deserve accurate history

Malaysians deserve accurate history

Dr. Ranjit Singh Malhi; Source: ‘The Star’, in his Letter to the Editor.

HISTORY is a factual account of significant events in the past that have shaped present-day society and the nation. It enables us to understand how today’s society and nations evolved.

Hence, in explaining the origin and current state of our nation and its plural society, one cannot ignore the role played by non-Malays, particularly the Chinese and Indians, in the making of Malaysia. For example, how can one explain the New Economic Policy without drawing reference to the economic development of Malaya under British rule?

Similarly, how can one account for the rapid economic development of Malaya before independence without taking into account the security provided by the British government and the significant contributions of the Chinese and Indian communities?

Make no mistake about it. Without British rule and the significant contributions of the Chinese and Indian communities, Malaysia would not be what it is today.

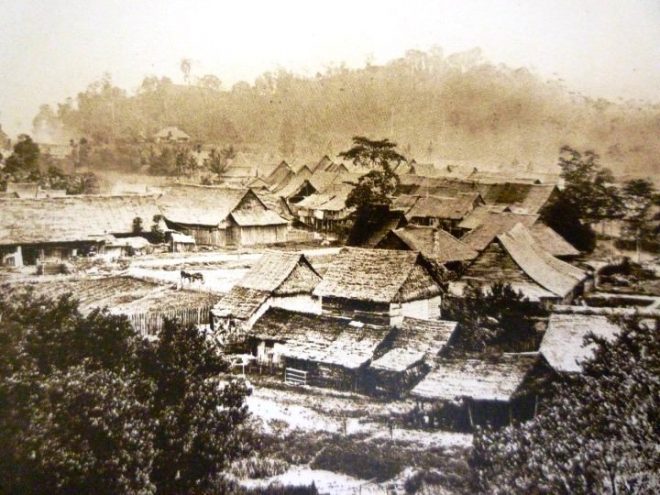

The Chinese and Indian communities are an integral part of our nation’s history. The Chinese community played a crucial role in the development of the tin mining industry and towns. In the words of Margaret Shennan, author of the book Out In The Midday Sun: The British In Malaya 1880-1960, “The impact of the Chinese upon Malaya was decisive. It was through them that urban life developed in much of the peninsula. Alongside their mining villages, they set up shops and workshops, and from these beginnings grew the main towns of the ‘protected’ states.”

It was Indian labour (mainly South Indians) that was the backbone of the rubber industry and primarily responsible for opening up much of what is today Peninsular Malaysia.

Rubber was the chief export of Malaya for several decades beginning from 1916; in 1957, rubber constituted 59% of the total exports of Malaya. Indian labour was also primarily responsible for building the roads, railways and bridges besides constructing ports, airports and government buildings.

For decades, rubber was the mainstay of our economy, and Indian labourers worked hard to drive the growth of rubber estates in Malaya.

Our history textbooks until 1996 provided a generally accurate and objective account of our nation’s origins and development. The trend of “rewriting” Malaysian history (Islamic and Malay-centric) started in 1996 with the formation of the Jawatankuasa Penerbitan Buku Teks Sejarah Tingkatan 1 & Tingkatan 2. Its members (more than 15 for each committee), including the writers and consulting experts of the textbooks, were all Malays. The three authors of the current Form One textbook (first published in 2016) are also Malays although the consulting experts are multi-ethnic.

Our current history textbooks are glaringly biased. First, they downplay the roles of the non-Malays in the development of our nation. For example, the previous textbooks used to mention adequately the contribution of the Chinese and Indians in the development of the tin mining and rubber industries. Now, it is given scant attention.

Chinese miners contributed to the development of Malaya, bringing about commerce and prosperity in many towns and cities.

Another example is that the current Form Two textbook (page 153) only refers to Yap Ah Loy as “antara orang yang bertanggungjawab membangunkan Kuala Lumpur (among those who developed KL)”.

All historians worth their salt will admit that Yap Ah Loy was primarily responsible for transforming Kuala Lumpur from a mining village into a leading commercial and mining centre after it was largely destroyed during the Selangor Civil War (1867–1873).

Indeed, Dr Ahmad Kamal Ariffin (a senior lecturer with the History Department of Universiti Malaya) recently commented that Yap Ah Loy’s “role in rebuilding Kuala Lumpur should be given its place in history textbooks. Yap’s name is synonymous with Kuala Lumpur because, if not for his contributions, the city may not be the national capital today.”

Interestingly, our earlier Form Four history textbook (second edition) published by Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka in 1979 provides a detailed account (about three pages) of Yap Ah Loy’s role in developing Kuala Lumpur.

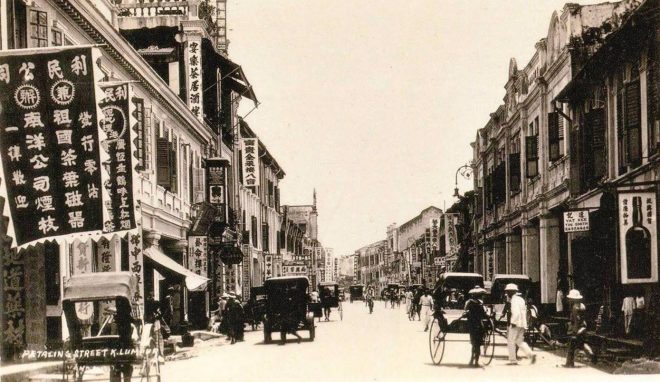

Bujang Valley Archaeological Museum in Merbok, Kedah, where a Buddhist-Hindu civilisation existed for a thousand years before the arrival of Islam to Malaya.

Second, there is a lopsided emphasis on Islamic Civilization. Five out of 10 chapters (about 40%) of the current Form Four history textbook deal with Islamic history. The earlier Form Four history textbook had only one chapter (about 17%) on Islamic history.

Third, the amount of text related to Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism in the current Form Four textbook has been reduced by more than 25% compared to the earlier textbook.

Fourth, our history textbooks do not tell the whole truth. For example, why can’t we state categorically that the founder of Malacca (Parameswara) was a Hindu prince from Palembang who maintained his faith until his death?

We must be proud of our multi-religious and multi-cultural heritage. Our history textbooks must tell the whole truth and not glorify a particular civilisation or group based upon half-truths.

In this regard, I applaud distinguished professor Datuk Dr Shamsul Amri Baharuddin who recently stated to the effect that we have downplayed the Hindu–Buddhist influence in the early history of Kedah. Archaeological remains show that there was a Hindu–Buddhist polity in ancient Kedah with the local rulers having adopted Indian cultural and political models – a fact which is apparently not highlighted in our current textbooks.

Our earlier Form Four history textbook (second edition) published by Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka in 1979 provided a detailed and objective account of Hindu–Buddhist influence in ancient Kedah, including facts such as “Kedah menjadi satu kerajaan berpengaruh India”, “Setengah-setengahnya (orang India) berkahwin dengan keluarga diraja” and “fahaman Hindu tentang beraja tertanam di dalam sistem kerajaan tempatan”.

Malaysians of all ethnic groups contributed to nation building, harmony, and security of our country.

We should all be committed to the writing of history that is accurate, generally objective and well-balanced that can contribute towards buttressing a sense of patriotism and pride as Malaysians. Let us adopt an inclusive approach which promotes national unity and not a divisive method which hampers nation building.