Buddhist Traditions

Buddhist Traditions

Vairocana Buddha. Bronze.

Restored during Edo period, 17th Century CE

Todaiji Temple, Nara, Japan.

Buddhism is a major world religion that developed from the teachings of the Buddha-the Awakened One. It is a uniquely insightful practice that is not based upon beliefs in divinity nor reliance on others for one’s salvation; but on developing right understanding and living a virtuous life to gain liberation from suffering.

Theravāda Tradition

‘Theravāda’ means the ‘Doctrine of the Elders’. This ancient sect is the sole representative today of the orthodox school of Buddhism. Sri Lanka has been the main seat of this tradition, and from there, Sinhalese Theravāda was brought to Myanmar, Thailand, Laos and Cambodia. In modern times, its popularity and spread have extended to Europe, the Americas and Oceania.

The Theravāda doctrine evolved in Sri Lanka 2,300 years ago from an earlier Indian ‘Hinayāna’ school. The emphasis of this doctrine is on self-development and gradual cultivation towards liberation. Theravāda focuses on the lives and teachings of the historical Buddha Sakyāmuni and His immediate disciples – the monastic elders.

Generally, Theravādin principles have a conservative spirit, but its practice has a dignified grace. The Sangha (monastic community) is held in high-esteem as serious practitioners of Dhamma. Lay devotees are expected to provide for the monks’ and nuns’ material needs, thus gaining for themselves spiritual merits. Nevertheless, Theravāda has taken a more egalitarian trait today as lay people are also becoming aware of the path, and are practising meditation with increasing fervour.

The Theravāda school preserves its teachings in the Pāli language. Its vast canonical compilation is called the Tipitaka, which comprises the Vinayapitaka (disciplinary code), the Suttapitaka (doctrinal discourses) and the Abhidhammapitaka (metaphysics). Theravāda also relies heavily on Pāli commentarial works, especially those by Buddhaghosa, compiled in the 6th Century CE.

The goal of Theravādin practice is the attainment of Nibbāna – freedom from the cycle of rebirth and suffering. One embarks upon the Noble Eightfold Path – the progressive cultivation of morality, mentality and insight until the arising of wisdom and realization of Truth. Thereafter, he or she is known as an ‘Arahant’ – one who has accomplished the extinction of defilements.

Mahāyāna Tradition

‘Mahāyāna’ literally means the ‘Great Vehicle’. It refers to the emphasis on helping to liberate a larger number of sentient beings from Samsāra – the rounds of rebirth and suffering, often with the employment of ‘skillful means’. Among the more ubiquitous present-day Mahāyāna sects are the meditative ‘Chan’ (Japanese, ‘Zen’) and devotional ‘Amitābha’ schools.

The Mahāyāna emerged in India two millennia ago as a movement (the Mahāsanghika) which aimed to be more accomodative of new ideas and regional differences in the interpretation of Buddhist doctrines. Due to its inclusive spirit, Mahāyāna schools gained widespread acceptance amongst the newer converts to the religion.

Mahāyāna teachers and monks carried their teachings to Central, Southeast and East Asia, whereupon it took on a Sinicised form. From China, Mahāyāna doctrines spread to Korea, Japan and Vietnam, where they remain the dominant sects of Buddhism practised to this day. The Mahāyāna schools’ vast corpus of sutras and shastras (commentaries) were also translated from Sanskrit into various vernacular languages, such as Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Bengali, and Javanese, among others.

The Mahāyāna practitioner’s goal is the attainment of liberation not just for oneself, but for all sentient beings. Thus, great emphasis is placed upon compassion, vows and aspirations. The Mahāyāna espouses the Bodhisattva ideal – a great being who lives with virtue, wisdom and compassion, and vows to be reborn many life-times for the sake of delivering others from suffering. The Bodhisattva cultivates the six “Paramitā” (perfections) of generosity, morality, patience, energetic effort, concentration, and insightful wisdom, and employs skillful means to guide others along the spiritual path.

The Mahāyāna has taken a cosmic view of Buddhahood and a conspicuous devotional path. Many Buddhas and Bodhisattvas are said to exist and their intercession can help beings in understanding the Truth and be delivered from Samsāra.

Vajrayāna Tradition

‘Vajrayāna’ literally means the ‘Diamond Vehicle’. Diamond, being a tough material, alludes to the incomparable strength and ability of the Dharma in cutting through all fetters and defilements. ‘Vajra’ also refers to the thunderbolt – it is thought that a powerful and sudden jolt obtained through special techniques can potentially destroy ignorance in a single lifetime.

Vajrayāna school evolved as a spiritual counter-culture to Mahāyāna scholasticism in early 7th Century CE India. It embraced Mahāyāna doctrines such as Śūnyata (’emptiness’) but transmitted them in special texts known as Tantra. As such, the tradition was also known as Tantrayāna.

Vajrayāna teachings entered Tibet in waves from the 9th to 11th Centuries CE. There, having come into contact with local beliefs, it acquired a distinctive esoteric and mystical character. According to its teachings, obstacles to realization of the Dharma can be removed by enigmatic rituals and through the intercession of an Enlightened being. The ‘power’ to conduct such rituals were transmitted from an adept teacher to a disciple through complex and codified initiation ceremonies.

The Vajrayāna school also adopted the general Mahāyāna pantheon of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, with a few additions of their own, including deities in female (yogini) or wrathful forms. Besides, there is strong faith in mahāsiddhas – saints who possess supernormal powers and are able to intercede to assist others in their spiritual quest; as well as the belief in tulku – a teacher reincarnate.

Although the Vajrayāna school is presently synonymous with Tibetan Buddhism, it is also widely practised in Bhutan, Mongolia, Ladakh and Nepal. It is also being disseminated globally by exiled Tibetan monks and emigrants. Tibetan Buddhism has a significant following in the West due to the practical, contemporary teachings of the 14th Dalai Lama, and other such charismatic monks.

Unity in Diversity

Over the course of twenty-six centuries, Buddhism has evolved into a myriad of traditions and practices. Yet, with all their diversities, Buddhists are united by their faith in the Three Jewels – the Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha. All Buddhists accept Sakyāmuni Buddha as their teacher, and the Four Noble Truths as fundamental teaching. What differs is not the ends, but just the means of gaining Enlightenment.

To the credit and eternal praise of Buddhism, despite the differences among its various traditions and schools of thoughts, Buddhists have never gone to war, nor expressed hostilities towards each other. Buddhist sects flourished alongside in peaceful coexistence across many countries and cultures, a feat still unmatched, and achieved by no other major religion in history!

The Buddha attained Enlightenment 2,600 years ago (in 588 BCE), at Uruvela (present-day Bodhgaya), India. A few weeks after His great awakening, the Buddha shared His realization with His five ascetic friends, and they became His earliest converts and disciples. Not long afterwards, the Buddha converted more than a thousand nobles and former fire- worshippers of Uruvela. These thousand- strong followers formed the pioneer Saõgha – the spiritual community of monks.

The Buddha spent the next 45 years preaching tirelessly until His passing away in 543 BCE. Even during His lifetime, Buddhism gained a great following of kings, nobles, merchants, and masses of common folks. High-caste or low, they were all drawn to the Teaching’s simplicity, practicality, candour and egalitarian spirit. In Buddha-Dhamma, people saw the truth of existence and the possibility of overcoming all suffering. In fact, Buddhism rapidly expanded to become the dominant faith throughout the densely-populated Ganges Valley by the 5th Century BCE.

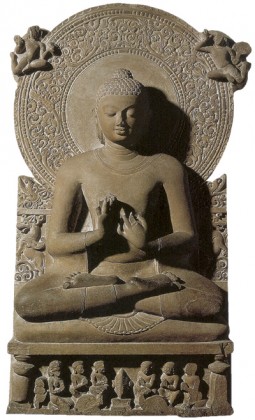

The Buddha started to preach the Dhamma two months after His Enlightenment. He first went to Sarnath near Varanasi to ‘turn the Wheel of Dhamma‘ (Dhammacakka), out of great compassion for the world.

Buddha preaching the Dhamma.

Sandstone. Gupta period, 5th Century CE

Sarnath Museum, Sarnath, India.

With the unification of the Indian Subcontinent under the Mauryan Dynasty, ruled by pious Asoka the Great, Buddhism became widespread throughout his empire. Asoka even sent missionaries abroad to as far as the Middle-east, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia. The patronage of succeeding Kushan, Gupta and Pala dynasties endowed Buddhism with great learning resources and a rich cultural heritage. Reputable Buddhist institutions such as Nālandā University – the earliest and largest in the ancient world – were teeming with scholars from all over Asia.

From its inception, Buddhism has always been a multi-ethnic religion. Due to its vast geographical expansion, Buddhism came into contact with many regional cultures and traditions. The various local beliefs and practices were often assimilated into Buddhism, which gave the religion a rich pan-Asian flavour and outlook. A result of such assimilation was the rise of variations in the interpretation of Buddhist Teachings. By the reign of Emperor Asoka in the 3rd Century BCE, there were 18 schools of Buddhist thoughts. These schools can be divided into two large groupings – the orthodox ‘Hinayāna‘ (comprising 11 doctrinal schools) and the reformist ‘Mahāyāna‘ (7 schools). Today, the Theravāda tradition survives as the sole representative of the orthodox group, whereas a few Mahāyāna traditions have continued existing till now.